Players rarely think about the planning behind a smooth story moment or a tight action sequence, but developers feel it the second something doesn’t flow right. A scene doesn’t hit, pacing drifts, or two team members imagine the same moment in completely different ways. This usually happens when teams skip the planning stage and jump straight into production.

A clear storyboard keeps this from happening. It gives everyone a shared picture of how a moment in the game should look and feel. You can test pacing, check narrative logic, and catch problems long before they get expensive.

In this guide of Polydin Studio, you’ll see what storyboarding really is, how it’s used in game development, examples from well-known titles, and a simple way to build your own storyboard without overthinking it.

Need Game

Art Services?

Visit our Game Art Service page to see how

we can help bring your ideas to life!

What Storyboarding Really Means in Game Development

A storyboard is a sequence of rough frames that shows how a gameplay moment, cinematic, or interaction should play out. It doesn’t need polished art. It just needs to show the idea clearly enough for the team to understand it.

Why games need storyboards:

- They help avoid costly rewrites and reshoots.

- They keep designers, artists, programmers, and writers aligned.

- They support consistent narrative pacing.

- They make it easier to prototype player experience.

- They remove guesswork during implementation.

Most teams think they’ll “remember the idea later,” but they rarely do. A storyboard turns a half-formed thought into something the whole team can use.

How to Build a Game Storyboard (Practical Step-by-Step)

Define the vision

Before drawing anything, get clear on what the moment should feel like. Is it tense, calm, or surprising? A couple of simple sentences are enough. This small bit of clarity helps everyone think in the same direction and keeps the scene on track once production begins. You are not trying to write something fancy here. You are just giving the moment a purpose so the rest of the decisions make sense.

Identify the key moments

Think about the big beats that move the moment forward. The player enters, notices something off, interacts with an object, triggers an encounter. You do not need to capture every small step. The goal is to mark the moments that define the rhythm. These beats act like guideposts. Without them, a storyboard usually becomes unclear because no one knows which moments matter most.

Create visual frames

Turn those beats into quick sketches. Keep them fast and loose. Simple shapes, arrows, and stick figures are more than enough. What matters is that someone can glance at a frame and understand the action right away. Try not to get stuck on details or drawing quality. The moment you slow down to polish a frame, you lose time and focus. A clear sketch will always beat a pretty one that took too long to make.

Include gameplay mechanics

This is where game storyboards differ from film. Add short notes about what the player can do or what the game systems are doing. For example, the player presses a button, an enemy reacts to sound, or a UI prompt appears. These notes turn your storyboard into something the entire team can use. They connect the visuals to actual gameplay, which is the real purpose of the board.

Review as a team

Once you have a rough pass, walk the team through it. Talk about each frame. Ask if the pacing works or if anything feels confusing. People often spot issues the moment they hear the sequence described out loud. This step saves a lot of time because it exposes problems before anyone opens the engine. Note that Silence in a review usually means confusion. Ask people to walk through the sequence in their own words. If they can’t, your storyboard needs work.

A storyboard gets stronger every time someone new looks at it, so treat feedback as part of the process, not a final stage.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

Overcomplicating the board

A lot of developers try to make their storyboards look like finished concept art. This slows everything down and hides the actual purpose of the board. When frames get too detailed, people start worrying about anatomy, shading, or perspective instead of the scene’s logic. The goal is communication, not artistic polish. A readable stick figure usually works better than a perfect drawing that takes an hour to make.

Ignoring player perspective

Teams sometimes storyboard a moment the way a film director might stage a shot. That can be useful, but if it doesn’t match what the player actually sees in gameplay, the board becomes misleading. For example, a dramatic zoom or angle might look great on paper but is impossible in the game’s camera system. Always ask: “If I were holding the controller here, what would I see?” It saves you from designing moments that break immersion or simply cannot be implemented.

Skipping iteration

A common belief is that a storyboard should be right on the first try. It almost never is. Most good sequences come from revisiting the frames, adjusting pacing, adding missing beats, or realizing a moment doesn’t land emotionally. Teams that avoid iteration end up fixing those issues later in the engine, where changes cost far more time. Storyboards are meant to be messy, disposable, and flexible.

Forgetting technical reality

Sometimes a storyboard shows camera moves, effects, or character actions that the engine cannot support, or that would require more time than the project allows. This disconnect creates tension between creative ideas and technical constraints. When reviewing boards, have someone who understands implementation in the room. It’s easier to adjust a sketch than to rebuild a scripted sequence.

Lack of collaboration

A storyboard made alone often captures only one person’s understanding of the moment. But games combine design, animation, programming, audio, and game narrative design. If these groups don’t see the board early, each one makes assumptions that drift apart. The result is a scene that feels disconnected or requires unnecessary rework. Reviewing the board together is one of the simplest ways to keep everyone aligned.

When You Should Use Storyboarding

- Designing combat encounters or boss fights

- Planning puzzles or platforming rhythm

- Mapping exploration flow and transitions

- Blocking out camera moves

- Prototyping cutscenes and intros

- Teaching new gmae mechanics

- Communicating scenes to new team members

Overall, If a moment needs clarity, storyboarding helps.

Where Storyboarding Helps the Most

Storyboarding is useful across all types of game projects management. Big studios rely on it for complex cinematics, large encounters, and major narrative beats. Indie teams use it to stay aligned without endless back-and-forth, especially when building puzzles, tutorials, or emotional moments. Educational games benefit from clear planning, and mobile titles use storyboards to shape onboarding flows, UI transitions, and short gameplay loops. No matter the scale, any moment that needs clarity or reliable pacing becomes easier to build once it’s sketched out first.

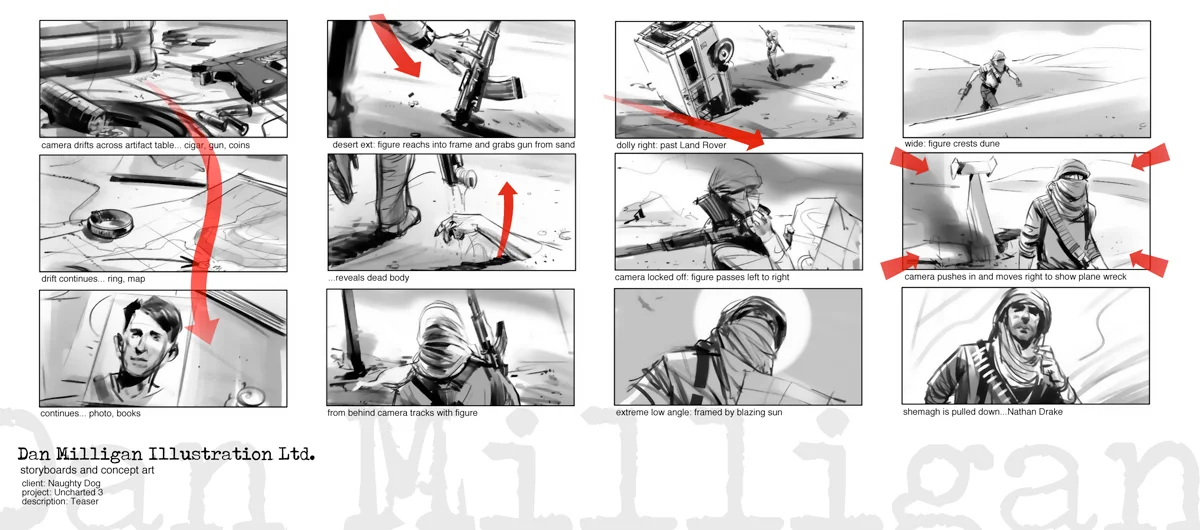

Real Examples of Storyboarding in Games

The Last of Us

Many of the game’s emotional scenes were planned first in storyboard form. Camera framing, character blocking, and even the tension-building moments were tested in rough panels before moving to full cinematics.

Hollow Knight

Enemy patterns, boss intros, and environmental immersion storytelling often began as loose sketch panels. These boards helped the team maintain mood and rhythm before translating anything into gameplay.

Celeste

Platforming rhythm was carefully storyboarded. Rough frames helped the team test clarity, tension, and timing long before building the levels in-engine.

Bottom Line

Storyboarding works because it makes ideas visible long before they become assets, code, or fully built scenes. It gives teams a clearer sense of pacing, helps spot weak transitions, and keeps moments consistent with the game’s overall direction. Even a rough set of frames can prevent hours of confusion later. When scenes matter, taking a little time to sketch them out usually gives the project a smoother path forward.

Sources

Polydin uses only high-quality sources, including peer-reviewed studies, to support the facts within our articles.

- Unity Technologies. (2024). Storyboarding for Games: A Guide for Visual Planning.

https://unity.com/how-to/storyboarding-for-games - Adobe. (2025). What Is a Storyboard and Why Is It Important?

https://www.adobe.com/creativecloud/design/discover/what-is-a-storyboard.html - Game Developer (formerly Gamasutra). (2023). Using Storyboards to Improve Game Design and Communication.

https://www.gamedeveloper.com/design/using-storyboards-to-improve-game-design - Storyboard That. (2024). How Storyboards Are Used in Game Design.

https://www.storyboardthat.com/articles/g/game-design-storyboards - CG Spectrum. (2024). What Is a Game Cinematic and How Are They Planned?

https://www.cgspectrum.com/blog/what-is-a-game-cinematic - ArtStation Magazine. (2023). Storyboarding for Games: Behind the Scenes of Visual Narrative.

https://magazine.artstation.com/2023/04/storyboarding-for-games - Into Games UK. (2024). A Beginner’s Guide to Storyboarding for Games.

https://intogames.org/news/a-beginners-guide-to-storyboarding-for-games

FAQs

Is storyboarding necessary for every game?

Not always, but it helps more often than people expect. Some very simple games work fine without storyboards because their moments are straightforward and easy to communicate. But once you have scenes with pacing, interactions, camera changes, or anything that relies on timing, a storyboard becomes useful. It gives the team a quick way to understand the flow before investing time in building it. Even small projects benefit from having a few rough frames for the moments that matter.

How do I start storyboarding for game development as a beginner?

Start small. Pick a single moment in your game, write one or two sentences about what should happen, then sketch a few rough frames that show the key steps. Keep the drawings simple. Use stick figures, arrows, and short notes. Focus on what the player does, what the camera sees, and how the moment moves forward. As you practice, you will naturally get better at spotting which beats matter and how to show them. The important part is clarity, not drawing skill.

What is the ideal length for a storyboard?

There is no fixed length. A good storyboard is only as long as it needs to be to explain the moment clearly. Some scenes work with five or six frames. Others, like complex encounters or emotional story moments, might need twenty or more. The goal is to cover the important beats without adding unnecessary panels. If someone can understand the flow without asking follow-up questions, the length is right.

What are the best storyboarding software tools in 2025?

There are plenty of options, and the best choice depends on how complex your scenes are and how your team works. Many developers start with simple tools like Photoshop, Procreate, or even Google Slides because they are fast and familiar. For more structured boards, Storyboarder by Wonder Unit is still a popular free choice. Tools like Clip Studio Paint, Blender’s Grease Pencil, and Toon Boom Storyboard Pro offer deeper features for teams that need camera planning or animation previews. The tool matters less than how clearly it helps you communicate the idea.