Anyone who has worked in the game industry knows how big of an influence trend-chasing is. And in this context, trend chasing doesn’t mean just paying attention to what’s hot and popular and using it in your own game. The word “chase” is of importance here because in it, there is an implication of a sort of mindless desperation, and that’s what we’re talking about here: mindlessly and artlessly looking for something popular to attach to your game, even at the cost of turning it into a Frankenstein monster, because you assume that’s what selling at the moment somewhere else, so it should work for you too.

Trend Chasing | A Byproduct of Investor-driven Economy

Let’s get to the heart of the issue: trend chasing exists because of the investor-driven economy of video games. What is the relationship here? Let me explain.

In the US, anyone who wants to make something big has to convince investors to invest money in it unless they can fund the project themselves or, for whatever reason, the government decides to fund it. This has been a hot debate for the past 200 years: who is better at funding big projects? The government, with its slow and bureaucracy-based but safe and solid method, or investors, with their chaotic and quick but result-oriented approach to doing things?

One could argue about different categories of projects individually. For example, in my opinion, tech-based startups work best in an investor-based economy because their fast-paced, result-oriented approach leads to quick and effective improvements, but medical and pharmaceutical companies need the bureaucratic approach of the government. After all, when we’re talking about people’s lives, looking cool to investors should be your last priority (as evidenced by the Theranos disaster, a healthcare startup that endangered people’s lives and destroyed 100 million dollars because Elizabeth Holmes, its CEO, wanted to be the next Steve Job).

But we’re talking about video games, which are entertainment/art. Those are subjective categories. You have objective metrics to determine why a certain car model or an iPhone model is better than its predecessor and then show that to investors to convince them. With video games, movies, or books, you don’t have that. Sure, you have a metric for sales or viewers, but that’s terrible for art.

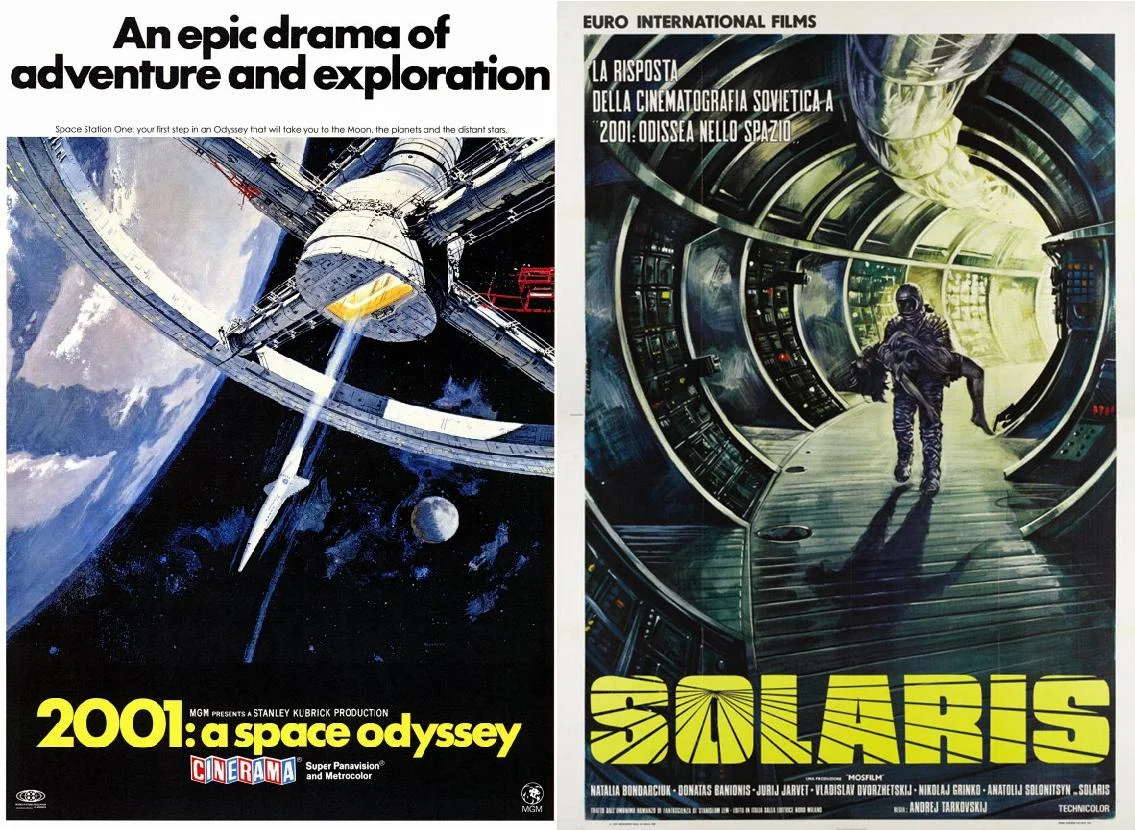

George Lucas, the creator of Star Wars, has made a surprising claim in one of his interviews: that Soviet filmmakers had more freedom than he had in the US when it came to making movies. How can that be? Regarding the US vs. Soviet Union, there shouldn’t be a contest for who was more free. But in his own words:

I do like movies, I love movies, and I know a lot of movies aren’t popular, and you can say that going in. One of the reasons I retired was so I could make movies that aren’t popular, because in the world we live in and the system we’ve created for ourselves, it’s a big industry. You cannot lose money, so the point is that you are forced to make a particular kind of movie. [Back when the Soviet Union existed, people asked me]: ‘Oh, but aren’t you so glad that you’re in America?’ I said, ‘Well, I know a lot of Russian filmmakers; they have a lot more freedom than I have. All I have to do is be careful about criticizing the government; otherwise, they can do anything.’ And so what do you have to do? You have to adhere to a very narrow line of commercialism. [Back in the 70s], they would have never let me make that movie if they knew what I was doing.

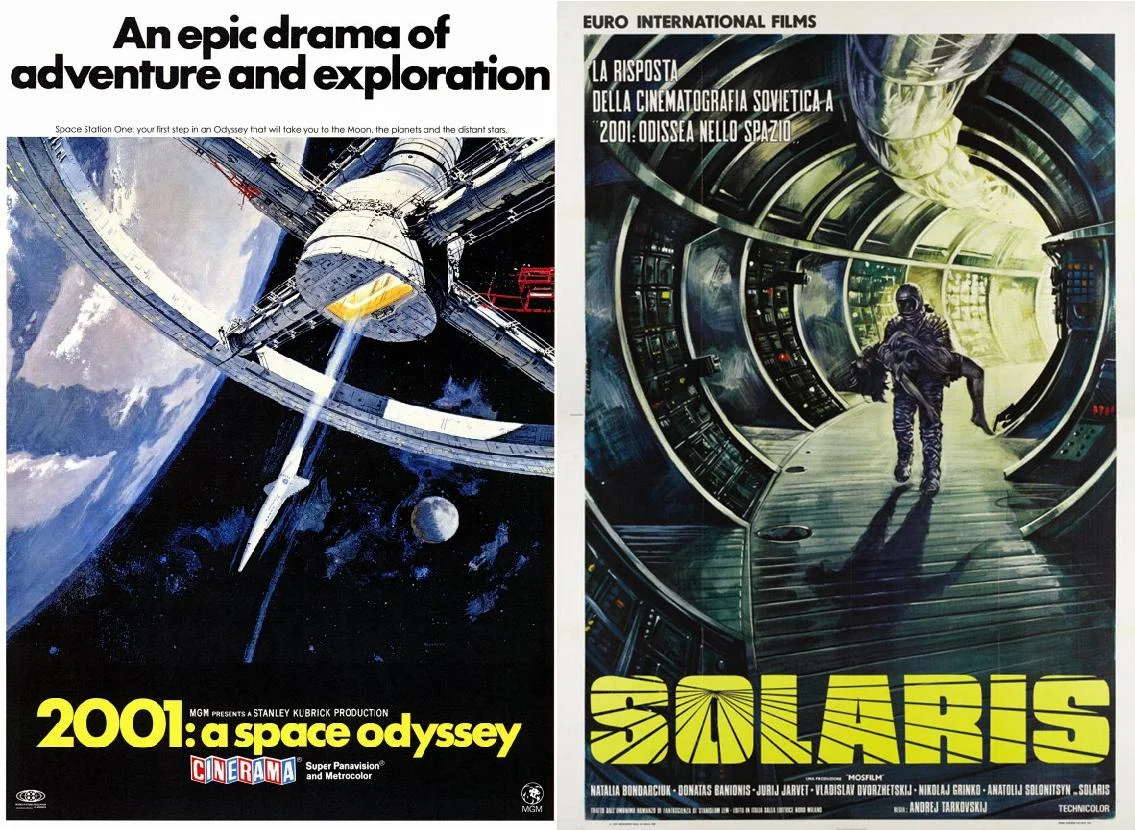

Lucas is talking about movies here, but what he’s talking about applies to the world of games, too, especially the line “narrow line of commercialism”. The Soviet art creation model had so many problems (the most notable being insane censorship). Still, one problem it didn’t have was that nobody expected a Soviet movie or a Soviet novel to make millions of dollars because there were no investors to keep happy. Therefore, a Soviet filmmaker had more freedom to include artistic merit in his work. Video game level design never got the chance to be made in that ecosystem, so we are forced to resort to movies for comparison purposes.

This is not to say we need to return to that model. Still, we need to address an issue: the narrow commercialist mindset of an investor that can help many purely result-oriented industries flourish but is a huge obstacle to creating art.

When meeting with potential investors, you have to promise them the world. You have to convince them that whatever you make with their money will be this huge thing that will create a mania and return their investment tenfold. Putting that aside, since most investors are strictly money people and most of their education is related to finances, “artistic quality” is not on their radar. If it makes money, it’s good. If not, throw it in the trash can.

Warren Spector: An Industry Legend Who Didn’t Care for Trends

Dealing with investors has always been challenging for creative people in the industry. One of the most interesting tales in this regard is about Warren Spector, creator of Deus Ex. You can read more about him in the first chapter of “Press Reset: Ruin and Recovery in the Video Game Industry” by Jason Schrier.

To make a long story short, Warren Spector had a legendary status in the gaming industry because of the great games he was involved in making. But you might find it shocking to know that he had a very hard time finding investors to make the games he wanted to make, and most of the time that he did find them, they would soon either withdraw or go bankrupt. With someone like Spector, you would expect that investors and publishers line up to finance his next project (except for one time; we’ll get to that), but that didn’t happen because he was too real for this business.

His first problem was that he didn’t care for the sales of his own game. In his words: “The number of copies I want to sell is N+1, where N is the number of copies I need to sell to make my next game.” His second problem was that he was very realistic and transparent, and he would list all of the issues his team could face in his presentations. Investors are kinda hostile towards pure honesty; this is why misleading promises, manipulation, “fake it till you make it” attitude and straight-up lying are so prevalent in an investor-driven economy.

For example, to convince an investor to give you a lot of money, you must make a big, eye-catching claim, like “Our game is going to have 1000 explorable planets!”. This looks good on promotional material, and the investor is happy. Still, when you have already got the budget and are close to the finish line, you quietly inform the public: “Only 10% of those are going to have living creatures in them”. This inconvenient detail will not discourage anyone from buying the game now that you have all the hype. The investors are not going to care as long as the game sells. But this is not something Warren Spector could do because he was no bullshitter.

His third problem was that he didn’t care for trends because he could see them for what they were: artificial milestones that could change or be taken over at any time. For example, after Deus Ex, he wanted to make a Western game, but Eidos, the publisher he worked for then, didn’t believe Western games could sell. Spector responded, “Western games don’t sell until someone makes one that sells”. And a few years later, Rockstar proved that by making Red Dead Redemption.

Trend Chasing | The Blind Leading the Blind

This brings us to another fatal flaw inherent in trend-chasing: chasing trends is all about people thinking they know something about an inherently unknowable phenomenon. Eidos marketing execs thought that Western games don’t sell based on some analysis that was probably sound. Still, the problem is that every time a game becomes so successful that it becomes a trendsetter, it is not doing what every other game was doing, it is fulfilling its potential. That’s why it became a trendsetter.

This is something that investors who push game developers to follow trends don’t consider. For example, when Junction Point, a company founded by Warren Spector, was making Epic Mickey 2, Disney, its owner, pushed the studio to change the game’s nature according to the month’s hottest trend. According to “Press Reset”:

Junction Point was struggling. The influx of new people triggered cultural conflicts, the time constraints caused a lot of stress, and Disney’s executives would frequently come in and ask the developers to experiment with whatever trends were making the most money that month. “We were exploring a free-to-play version; an always-online version,” said [Chase] Jones. “Whatever the whistle of the day was, we had to create another deck that showed: Should we or shouldn’t we do this?” Games like FarmVille and League of Legends were making billions of dollars, and Disney wanted to emulate those successes.

Do you realize how demoralizing this is? To work on a single-player story-based game and suddenly have your publisher suggest you turn it into a F2P game because FarmVille and League of Legends are raking in the money? For God’s sake, What does Epic Mickey 2 have to do with League of Legends and FarmVille?

The depressing thing is that publishers and investors think like robots regarding trends, meaning they have a good grasp on what has happened before and now, but they have no notion of what COULD happen. And most great successes are achieved by people who think that way. Marty Sliva, in the Escapist article “AAA Games Need to Stop Chasing Trends and Start Making Them,” has described this nihilistic cycle very well:

Stop me if you’ve heard this one – a hot new game comes out of nowhere and suddenly becomes a massive hit. It has an idea, theme, or hook that resonates with a wide audience, and we then have to spend the next several years watching countless developers and publishers try to recapture that lightning in a bottle, until things eventually hit a saturation point and they realize that people aren’t interested in that idea, but are now all in on this new hot game. The cycle repeats, and it sometimes feels like we’re doomed to live in a world where the biggest AAA game developers on the planet are chasing trends instead of making them.

I described this cycle as “nihilistic” because: 1. It takes away the opportunity from bold, ambitious, and creative authors to make interesting games 2. It dumbs down the public’s taste because it constantly feeds them the same thing until they can’t take it anymore. And to make matters worse, the long development cycles of most games almost guarantee that whatever you think is the trend at the beginning of the production will fall out of favor by the end. A recent example is Final Fantasy XVI. Its developers started conceptualizing the game in 2015, at the height of Game of Thrones popularity, while right now, in 2023, GOT style of fantasy has stopped being trendy because of the show’s terrible season 8. So the similarity might not seem as favorable as the developers hoped for in the beginning.

Sometimes, All You Need is a Patron

I mentioned something about publishers and investors not lining up to finance Spector’s next big project except for one time: that one time was when he made Deus Ex, his most important game and one of the greatest of all time.

As the story goes, back in 1997, Looking Glass Austin, the studio Spector was working in at the time, shut down. He started negotiating with Westwood to make an RPG based on their popular RTS franchise, Command & Conquer. Everything was going well until he got a call from John Romero, the bad boy of the 90s gaming world. He shook the gaming world – and, to be fair, the world at large – by creating Wolfenstein 3D, Doom, and Quake in id Software, and after he quit id Software, he founded his studio: Ion Storm.

Romero had made a fortune at id Software because all their games sold like hotcakes. He also had a legendary status and a very bold and forceful personality. So he could throw his weight around. In 1997, he called Spector and told him to work for him at Ion Storm. Spector told him that he would make the Command & Conquer RPG. Romero was so determined that he drove to Spector’s office and made him an offer he couldn’t refuse. In the words of Jason Schrier:

Romero told Spector to say no to the Command & Conquer deal and to come to work for him instead. But it was too late, Spector said—they were about to sign. So Romero drove from his office in Dallas to Spector’s in Austin and slapped down the godfather offer of all godfather offers. “Unlimited budget, a bigger marketing budget than I’ve ever had,” said Spector. “Make the game of your dreams with no interference from anybody. Who says no to that?”

Isn’t it an interesting coincidence that a creative talent made one of the best games of all time when one of his peers – who knew his work and respected his talent – begged him to make the best thing he could make, with no interference from anyone?

What made this deal so special was that Spector didn’t have to convince anyone who didn’t know anything about video games to give him money to make video games. I’m sure there is a certain absurdity in that scenario that isn’t lost on anyone who had to go investor-chasing. It was John Romero, an industry legend, using his fame and money to allow another industry legend to make something really good.

I know this is an exceptional case, and you can’t expect all the money people to be kindred spirits like John Romero. I can’t help but feel that this is the best condition in which greatness can foster: to have people who recognize talent to determine which creative project gets money, not people whose only obsession is quarterly sales. After all, we can’t forget that some of the best works of literature humanity has ever produced were created thanks to the support of one rich patron with good taste, not a publishing company that wanted to sell 50 copies instead of 30.

Conclusion

The point of all this is simple: every creative work has a distinctive soul that makes it what it is. This soul’s greatest opponents are the “trends” of the time. Sometimes these trends completely take over that soul and shorten its expiration date significantly. Sometimes they tarnish it, making it feel outdated after a while. If you have experienced creative work in the past (in any format), you can clearly see how badly the author’s trend-chasing can influence how it is perceived. A creative work that uses trends and inspirations appropriately is the kind of work that can stand the test of time. But even if you don’t care about standing the test of time, you must at least care about your work being noticed when it is released. Trend chasing cannot even guarantee that. Because one needs to stand out somehow, and looking like a copycat of every other game out there is not the way to do it. So no matter how you look at it, no good can come out of trend-chasing: mediocrity is the best it can achieve.