Imagine walking through an empty mall at 3 AM. The fluorescent lights are off, the escalators have stopped and every store is locked. It feels like a familiar place stripped of its purpose, leaving behind a strangely unsettling emptiness that has become the foundation of modern horror aesthetics.

Many people recognize liminal spaces as eerie or unsettling, but they do not understand why such ordinary, harmless environments can evoke such strong feelings of dread and discomfort.

Liminal space horror reveals something deeper about modern life. These vacant corridors and silent rooms are not frightening because of monsters or darkness, but because they remind us of loneliness, aimlessness and the breakdown of meaning in fast paced modern society.

This article explores why liminal spaces have become a staple of contemporary horror, how culture and psychology shape this aesthetic and why video games and internet folklore have embraced this unsettling atmosphere so strongly.

It’s All About Late Stage Capitalism… Again?

“Liminality” is a state of in-betweenness. If you think about it, a lot of modern life is about being in liminality. Airports, offices, stairways, they all exist to connect us from one place to another. But with each passing year, a question lingers on people’s mind: where is the destination? There are many people whose life is reduced to liminality: going from one meeting to another, from one office to another, from one city to another. But they could be busy doing the most meaningless thing and they have no way of knowing, because life is going so fast there’s no time to stop and question it all.

Now, these liminal spaces remind us of the hollow nature of the busy world we have made for ourselves. The picture of an airport without passengers, a school without children or a mall without shoppers reminds us of a stage set without actors; it reminds us that how much of a façade everyday life can be. And when this façade is gone, all we are left is elaborate functional emptiness on a massive scale. Think of all those abandoned Olympic venues that were made for 2002 Athens Olympics. The pictures of those once-majestic-now-decaying structures are haunting. Maybe part of it is the realization that how much money and resources were wasted there, for a short-lived vanity project. This waste of resource is scary to us. Partly because we are scared of running out of it, and partly because we realize once all the glamor and glitz is gone, only emptiness and decay is left.

Liminal spaces connect nothing to nowhere. And for the people who are in their 20s and 30s, these spaces represent a painful internal condition: we are in a state of uncertainty and aimlessness like these spaces. There are no careers anymore; only gigs. There are no family ties anymore; only shallow and transitory relationships based on mutual benefit; there is no meaning anymore; only algorithm. This acting gig we do on the world stage is starting to disturb us. So, we like to imagine what would happen if we all suddenly stop playing. The result is the monster we face in our generation, which is not a zombie or a werewolf: just a vast empty space, devoid of meaning, devoid of context, devoid of its main players: us.

In a way, Jean Baudrillard, the French philosopher, talked about all of this. Another name we can give liminal space horror is Baudrillardian horror, the terror of realizing that the world has become a simulation of itself. In Baudrillard’s theory of the “hyperreal,” we no longer experience things directly but through images and symbols that have replaced the real so completely that the distinction no longer matters. Liminal spaces disturb us because they momentarily break that illusion: they are the physical glitches in the simulation, where the machinery of modern life keeps running even after meaning has drained out. They confront us with the truth that much of what we take as “reality” is just an elaborate performance sustained by habit and consumption.

And perhaps that is why these empty corridors and blank rooms feel supernatural: they are not haunted by ghosts, but by the absence of purpose. They remind us that our entire civilization might already be a kind of haunted house, full of automated systems still pretending to serve human needs long after the human story has ended. In the glow of the fluorescent light, we are forced to see ourselves not as players on the stage, but as echoes wandering through the leftover scenery of a world that forgot what it was built for.

Liminal Horror Weaponizes Our Brain Against Itself

Our brain likes to find patterns. Liminal spaces use this impulse against itself. When we see an airport, we expect it to be buzzing with activity, be full of people. An empty airport signals danger to our brain: this place should be full of people. Since it’s not, that means something terrible has happened there. Something is deeply wrong.

That’s the source of horror in liminal spaces. It implies horror through negation. An empty airport could imply a mass pandemic that has depopulated earth and destroyed civilization, an empty hallway implies that if someone or something kills you there, there won’t be any witnesses; an empty mall signifies an unknown threat; the presence of a predator somewhere deep in that space that has driven any sign of life away.

So mechanically and functionally, liminal space makes it very easy to startle an overactive imagination. On the surface level, it makes it perfect for jump scares. Since liminal spaces are pristine, monotone, long and straight-lined, you can make something jump at the player and completely catch them off-guard. But like all forms of horror, liminal space has a deeper layer that tells us something about the living condition of the people who found it scary. Liminal spaces represent our conditions as the aimless, futureless citizens of the 21st century and showcases our anxiety about living in a world that is losing all meaning, but retaining all functions.

Liminal Space in Video Games

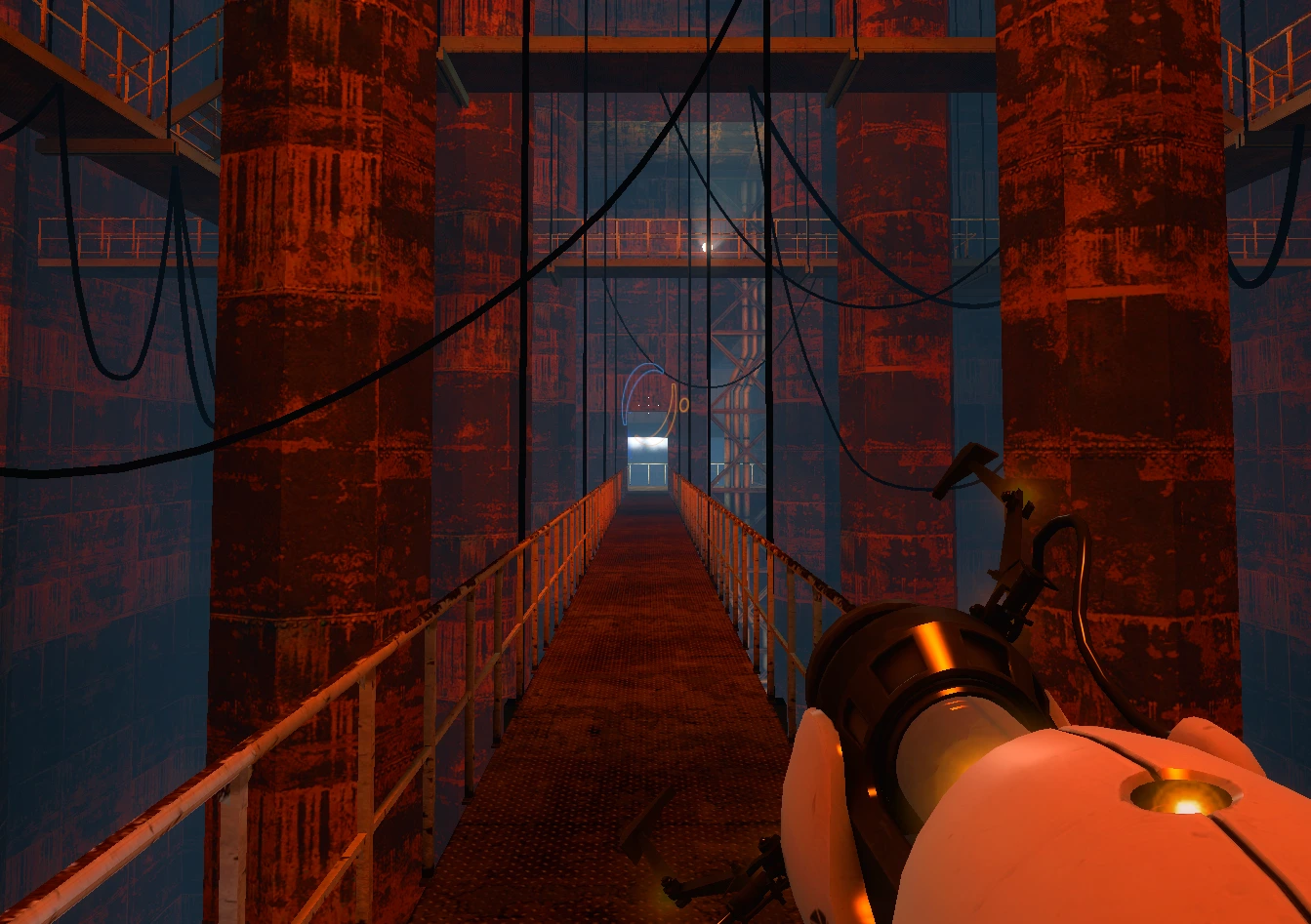

While liminal space horror is only identified as a real thing recently, its origins go way back to the 1990s. One could argue that the original System Shock (1994) was the progenitor of liminal horror, because it was set in a clean, vacant space station that was fully functional, but devoid of all its original intent and filled with horrible monsters. But the first game that delivered liminal aesthetics in the way we recognize was Half-Life (1998). Half-Life is set in a secret science facility that goes through a catastrophic failure of a science experiment that opens a portal to another dimension and paves the way for aliens to enter our world.

Half-Life’s world design was very real and very wrong. The long industrial corridors, the pristine vacant office buildings, the vast empty warehouses filled with containers, the eerie silence of the facility sometimes being invaded by an atmospheric ambient music, it was all very “liminal horror” before it was even a thing.

Valve turned up the liminal aesthetic up to eleven in Portal 1 & 2. Unlike HL1, which was filled with enemies and NPCs, in Portal games, the highly sterilized environments were devoid of human presence (apart from the main player). While the tone of both games is mostly comedic, the solitude and the sterilized functionality of the abandoned facilities the games take place in can result in some intense unintentional eeriness.

Apart from Valve games, liminal space aesthetics was heavily featured in The Stanley Parable, the ultimate meta game that was an elaborate commentary on player agency in video games. The game is about an office worker named Stanley who can either do what the narrator says or do his own thing and bask in the absurdity and post-modern humor that follows. Despite the game’s humorous tone, the highly sterilized office environments creates that uncanny “liminal horror” feeling which has led to some people asking if this game is scary, despite it being far from that.

We can see the usage of liminal horror aesthetics in horror games like Silent Hill 2, with its haunting hallways and hospitals. However, it would be cheating to consider SH2 a part of the category, because it’s a straight up horror game with a dark artistic art direction that goes against the sterility and vacancy we associate with liminal horror nowadays.

The Backrooms: The Ultimate Liminal Horror

The culmination of liminal horror aesthetics is an internet legend/mythos called the Backrooms. And it all started with a 4chan post.

On May 12, 2019, on the imageboard 4chan (/x/, the paranormal board), a user posted a thread asking people to share “disquieting images that just feel off.” Someone posted that now-famous picture — a yellow, empty maze of office rooms — along with this caption:

“If you’re not careful and you noclip out of reality in the wrong areas, you’ll end up in the Backrooms, where it’s nothing but the stink of old moist carpet, the madness of mono-yellow, the endless background noise of fluorescent lights at maximum hum-buzz, and approximately six hundred million square miles of randomly segmented empty rooms to be trapped in.”

This humble post miraculously led to the creation of a popular concept called the Backrooms, which simply put, are breaches in reality. The term “noclip” is important here, because it’s a video game term that refers to passing through solid objects and boundaries of the game when you use a cheat code or run the game in maintenance mode. The premise here is that reality is like a corrupted software and if you break its programming, you end up in some sort of limbo/after-life that looks like an infinite, maze-like plane of monotonous, liminal spaces that exist beneath or beyond our world. That’s a pretty trippy, isn’t it?

Gamers have expanded this idea and created a whole lore around it. One part of the lore is the setting. The Backrooms are divided into different categories. For example, level 0 is The Lobby: The classic Backrooms; monotonous office spaces looping infinitely. Time and space behave inconsistently here. Level 2 is The Pipe Dreams, with long maintenance tunnels, extreme heat and machinery noise. Level 4 is the office complex: a safer area that looks like an old computer office and it’s a parody of modern work life.

If you want to create a game or a Youtube video about these settings, you can populate them with monsters that include, but are not limited to:

- Hounds: Deformed, humanoid predators.

- Facelings: Human-shaped beings with blank, featureless faces.

- Skin-Stealers: Entities that wear human skin to imitate people.

- Smilers: Shadows with glowing white grins.

If you have ever watched a viral liminal horror video game clip, you probably have seen streamers screaming and running from these creatures in one of the aforementioned settings. However, liminal space is most effective when the monster is not there, but you expect it to be.

Bottom Line

Liminal space horror resonates because it reflects a part of ourselves we rarely confront. The empty malls, silent offices and endless yellow hallways feel uncanny not because of supernatural threats, but because of what they reveal about our own world and our own condition.

They show us a reality stripped of purpose, running on autopilot long after meaning has drained out. Working with these themes over the years, I have found that the true terror of liminal spaces comes from how closely they mirror our daily lives: the routines, the transitions, the empty performances we call productivity. That is why these still, quiet spaces feel haunted even when nothing is there. They remind us that the scariest thing is not a monster chasing us, but the possibility that modern life has become a stage set without actors, waiting for us to question what we are really doing behind all the hum of fluorescent lights.