In the realm of gaming discourse, terms such as “atmospheric” and its kin, “immersive,” have evolved into buzzwords casually tossed around without a thorough examination of their true essence. While not devoid of meaning, these words often fall into the category of “I know it when I see it,” demanding a closer look to unravel their complexities. In the context of atmospheric horror, this exploration becomes particularly intriguing, prompting us to delve deeper into the nuanced layers of fear and suspense that define this captivating genre.

The Complexity of Atmosphere

I have reflected on this word, and I have come to the conclusion that the atmosphere is caused by feeling the shadow of something over you, without actually confronting it. Just think about the most cliched atmospheric scenario that humans go through: when you are sitting on the bus, it’s raining outside and you’re looking out the window.

There is nothing tragic about this image; it’s just the mundanity of life in its purest form, but for some reason, it can ruin your mood like nothing elseIt’s like you’re feeling the shadow of the loneliness of the human condition, the transience of life and moments, the finality of death and all sorts of poetic and philosophical concepts without actually being confronted by any of them. The best word to describe it is melancholy.

The Deeper Meaning of Melancholy

The word melancholy itself has become synonymous with a sort of inexplicable sadness that comes out of nowhere. You don’t feel melancholic when you watch Titanic. If that movie affects you emotionally, it’s just direct sadness and tragedy. You feel melancholic when you watch Lost in Translation. Both movies are about the pain of losing a stranger you had an intimate connection with, and in many ways, Lost in Translation is far less tragic than Titanic.

Atmospheric Satisfaction

But the sadness it leaves you with runs deeper. I would describe Lost in Translation as atmospheric, but not Titanic. Now, don’t get me wrong; I’m not saying Titanic should have been atmospheric. Being atmospheric doesn’t fit every kind of artistic work. But when it comes to the artistic experience, works that are atmospheric will always be more satisfying and memorable than those that aren’t.

what is the difference between horrific vs. mundane

I’m here to argue here that this is also the case with the horror genre. There is a difference between normal horror and “atmospheric” horror. They are not necessarily separate from each other, but elevating normal horror to atmospheric horror is a different ordeal. Sometimes, it might be at odds with a standard horror experience.

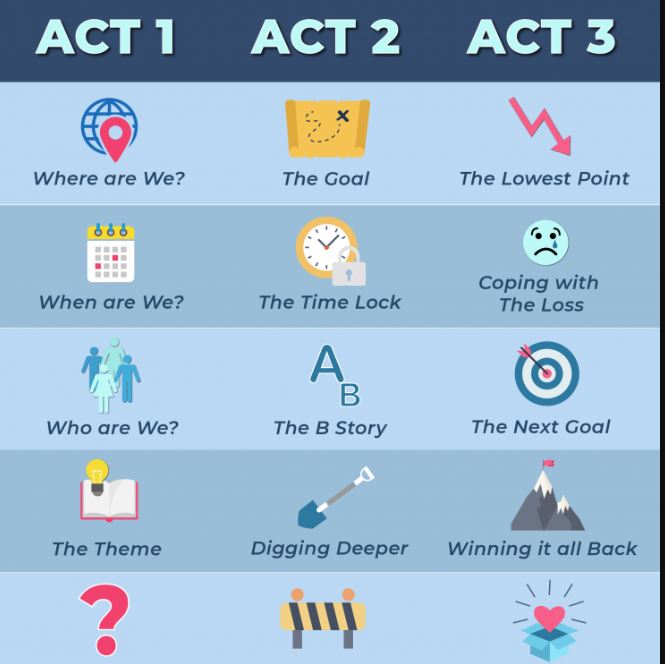

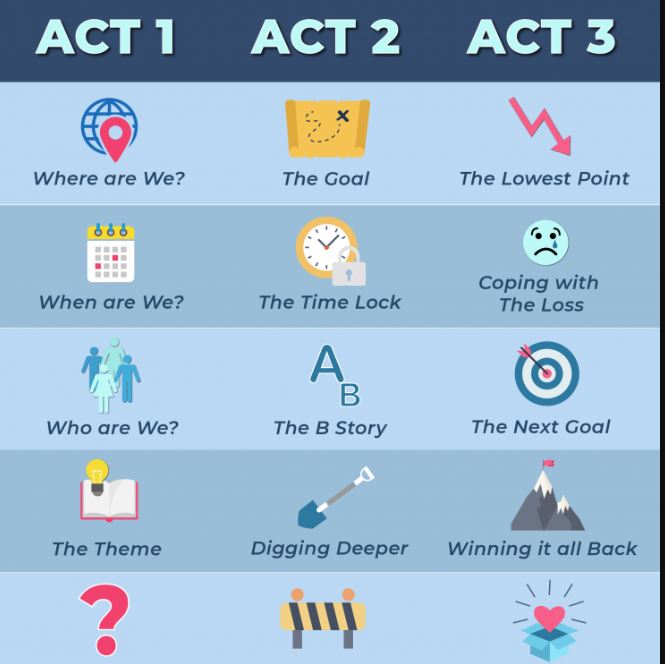

Think about your average horror movie for example. Most of these movies have a similar structure:

- In the first act, the characters are shown having a normal, mundane life

- In the second act, the horror element (the ghost, the serial killer, the cannibal family) starts messing with the main characters, challenging their sense of mundanity

- In the third act, there’s a full-blown confrontation between the main character and the horror element and this tension is resolved either through victory or defeat.

This style of horror works well at creating scary moments, which is the purpose of this genre. But it has a hard time being atmospheric. Why? Because as I said earlier, the atmosphere is caused by feeling the shadow of something over you, without confronting it, but in this style of horror, confrontation is inevitable and when it happens, nothing can go back the way it was.

This is a key point, because in my definition of atmospheric horror, you can confront the horror element – and it can be really scary – but the story has to be structured in a way that makes it possible for the characters – and you – to go back to the mundane after the confrontation. In other words, in atmospheric horror, there’s not a one-way road from the mundane to the horrific, but the audience traverses between the two realms seamlessly, to a degree that they might not even be able to tell the difference between the two.

The reason this dynamic is so effective at creating atmosphere is that horror is mostly based on something extreme and shocking. And once that initial shock is over, all you’re left with is a sense of danger. You either evade the danger or succumb to it, but once it’s over, it’s over.

On the other hand, creating a mundane environment with the possibility of horror invading it builds tension and suspense. This mundanity creates a sense of familiarity and comfort for the audience, which makes the sudden intrusion of horror all the more jarring and terrifying.

But the idea of returning to normalcy after horror invades is important too as it allows the audience to relax and collect themselves, and the thought of horror invading again creates a constant sense of unease and dread. This creates the atmosphere of horror that we’re talking about. Most feelings are temporary and fleeting, but atmospheric horror makes sure the horror you felt leaves a residue on your soul. A perfect atmospheric horror is always accompanied by a sense of unease, even after the horrific encounter is over and you are sure you’re safe for now.

The video that made me think about atmosphere in this way was How Vampire The Masquerade Bloodlines Creates The Perfect Atmosphere by the Youtube channel, Gamedev Adventures. The main thesis behind this video is that the reason why Bloodline’s atmosphere is so celebrated by the game’s many fans is the way it transitions between radically different settings in a short amount of time.

Explore diverse areas of atmospheric contrast in game locations

in the first section of the game, we have 3 different locations:

The Asylum Nightclub

Kilpatrick’s Bail Bonds

The Oceanhouse Hotel

All 3 of these places have a certain mood. The Nightclub is a crowded, energetic and decadent place filled with people dancing while nightclub music is booming in the background. The owners of the nightclub are two weird sisters who happen to be vampires.

Kilpatrick’s Bail Bonds is a dull dead place whose owner – Kilpatrick – is into messing up guys who don’t pay their debt in time. He also really looks like someone who is into the bail bonds business. There is no music in this place; just a radio show played in the background.

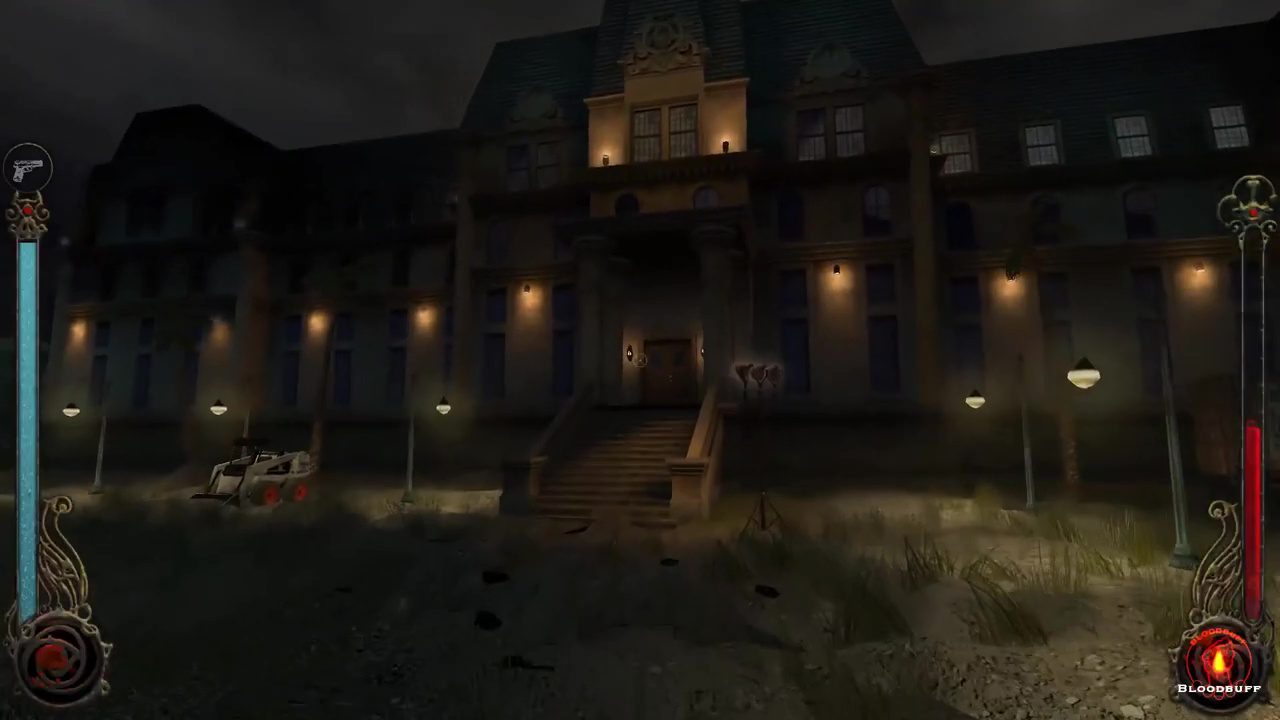

Then there’s Oceanhouse Hotel, which is a location straight out of a horror movie. It’s a spooky abandoned building in which all sorts of supernatural phenomena occur: light bulbs blowing up, furniture moving around, pans and pots flying in the air and damaging you on the way. As soon as you enter the front yard of the hotel, spooky music starts playing.

The distance between these locations is very short; maybe just a minute. But each one is so distinct they could belong to a different game altogether.

In one of the game’s quests, one of the sisters who owns the nightclub asks you to go to the Oceanhouse hotel and retrieve something for her. When you leave the club, the last thing you see is the image of people dancing and having fun without a care in the world.

A short while later, you go down to dark and gloomy sewers and you come out in the front yard of the Oceanhouse hotel. Now Oceanhouse hotel, by itself, would be a scary place, but what makes it special is that after you’re done with it, you have to go back to the nightclub to report your findings. When you come back, nothing has changed. People are still dancing, the music is still booming, the bartender still looks bored, but something has changed inside you. Now you look at this place differently. The carefree people dancing without a care in the world now look like the embodiment of the phrase “ignorance is bliss”. They are knee deep in mundanity, without realizing what kind of horror is going on around them. This transition between the horrific and the mundane is exactly the ingredient behind the game’s heavy atmosphere.

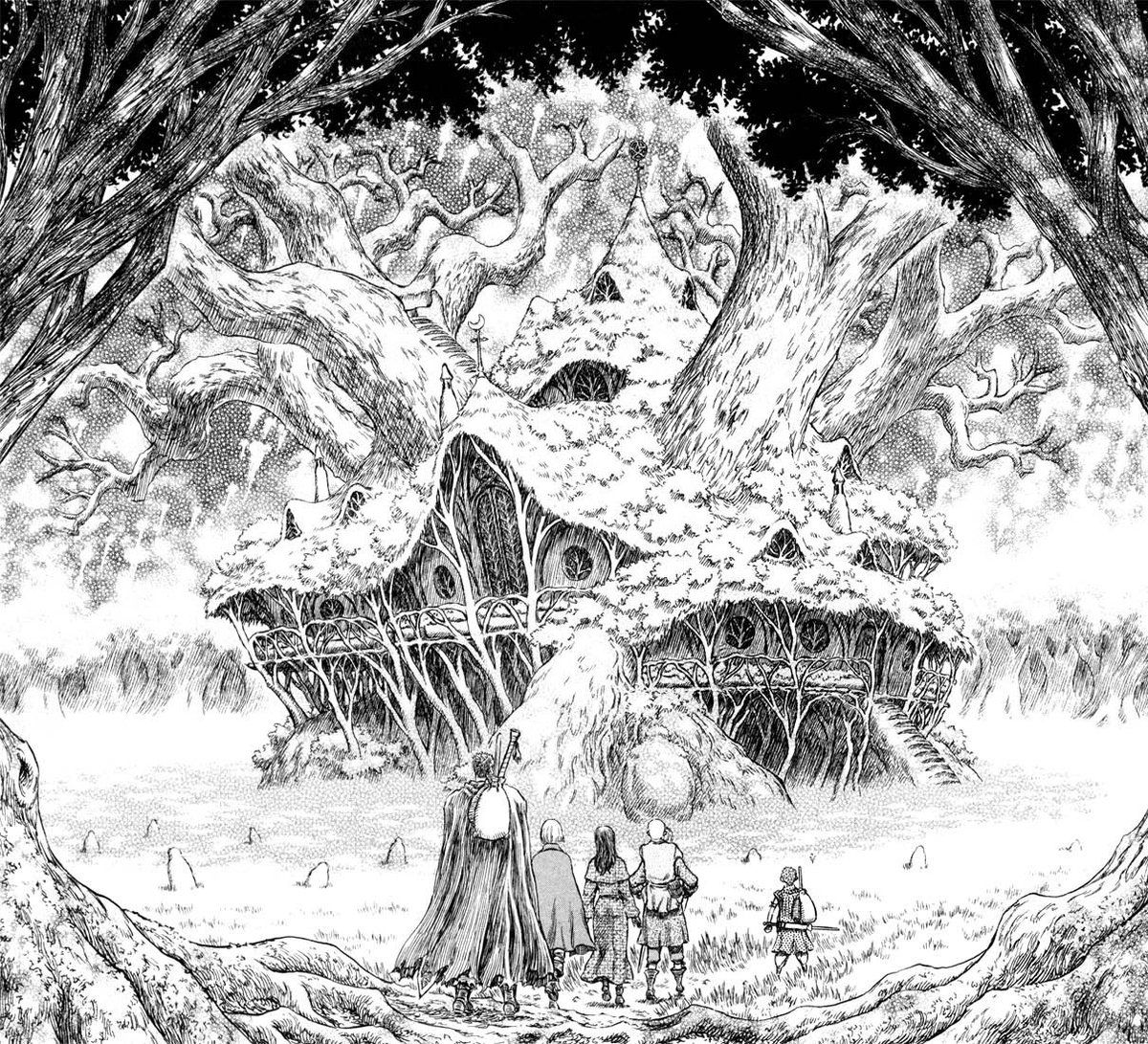

As the video was making the case for Bloodlines, something clicked inside my head. I recognized what the video was talking about in another game that I had played and I’ve always considered it to have one of the best atmospheres I have ever experienced: S.T.A.L.K.E.R.: Shadow of Chernobyl. And it’s not just my opinion. The game is famous for its atmosphere.

S.T.A.L.K.E.R. is another game that relies heavily on:

- Being immersed in the mundane

- Face shock and horror

- Going back to the mundane again

Most of the environments in the game are moody and gloomy, but nothing too crazy. Most of the time, you’re fighting either humans, animals or mutated creatures. The Zone, the setting the game takes place in, is heavily militarized. Everywhere, you can find mundane elements like outposts, camps, garrisons, etc. In some of the camps, Stalkers seem very chill, playing guitar and chatting up. In the very first Stalker settlement, there is a guy named Sidorovich who is the personification of the “greedy materialistic trader” archetype.

While STALKER is not a horror game in the traditional sense, there are two locations in the game that are straight up horror: Lab x16 and Lab x18. Out of these two, Lab x18 is infamous for being specially scary. As you overcome these locations and come back to the mundane and relative safety of Stalker camps and military outposts, you carry the horror you experienced in those underground labs with you, and you can’t look at guitar-playing Stalkers and the Materialistic Sidorovich the same way again. You might feel alienated from them, because their mundane world is so far from what you have experienced, or you might start appreciating them more, because their mundanity is exactly the safe space you need to feel around yourself.

The transition from Asylum Nightclub to Ocenhouse Hotel to Asylum Nightclub again that is discussed in the video has an almost identical effect to the transition from the Zone to Lab x18 to the Zone again that I described myself.

You might argue that visual and audio design play a huge role in making these games atmospheric and it’s not just about transition between mundane and the horrific. It’s true that visual and audio design play a huge role in making something seem atmospheric, but my argument is that for this atmosphere to have a long-lasting effect, it needs to engage the player on a thematic level, not just a sensory one.

A good example of this is Fallout 1 & 2. In terms of visuals, these games look so dated you could torture your average Fortnite player with their graphics. There is really no artistic direction. You are just a pixelated sprite walking around in samey environments made up of hexagons. But these games also fit the description of “atmospheric horror”, as I described here.

The way these games work is that there’s a world map, which consists of various locations. Moving between these locations takes days or weeks in the game’s world, but for you, it’s just a couple of seconds (unless you’re faced with a random encounter). But the atmosphere of each location is radically different, and jumping around between them definitely creates that “transition” effect.

For example, in Fallout 1, you start at Vault 13, a super-advanced underground bunker. The Overseer asks you to go find a water chip for the vault, otherwise they will run out of water in 150 days.

When you get out of the vault, the first location you come across is a very small impoverished village called Shady Sands. The simplicity of the villages stands in stark contrast with how advanced your own vault was. It gives you the feeling how messed up the world outside of your own safe space is.

After Shady Sands, you go to Vault 15 to see if you can find a water chip there. Vault 15 is an abandoned destroyed vault filled with rats. The messiness of this place further emphasizes your vault – Vault 13 – as a safe space and how good your own people have it there.

From here on, the game opens up a bit and you can visit different locations with your preferred order. All of these locations are a mix of mundanity and depravity and even straight up horror.

For example, In the same vein as Bloodlines and S.T.A.L.K.E.R, Fallout 1 also has one location that is meant to be explicitly scary: an optional location called “the Glow” which is extremely radiated and just staying there for too long, without a lot of anti-radiation medicine, is fatal. The fans of the game probably remember how stressed they got by receiving the same message over and over again: YOU’VE RECEIVED A LARGE DOSE OF RADIATION.

The whole place is just one big hole in the ground from which you have to descend with rope. As soon as you enter the Glow, a haunting music starts playing that immediately establishes a sense of horror and dread. Even though the Glow is just an empty radiated underground lab, it makes you scared just by being in it. The fact that its location on the map is far from other locations also contributes to this feeling.

From these examples, it might seem that the only kind of game that can live up to the ideal of “atmospheric horror” is a game that:

- Is not a full-fledged horror game and only has horror elements

- Should have an open-world or semi-open world structure, because in linear experiences, transition between mundane and horrific doesn’t happen dynamically

Both of these qualities help a game to be more atmospheric (and open-world horror is definitely a genre that needs to be explored more), but even in pure linear horror games, this dynamic has been used in a more limited way.

For example, the safe rooms in Resident Evil 1 are a good example. Resident Evil 1 takes place in a creepy mansion filled with zombies and monstrous dogs. Each room you enter creates tension, as you wonder what kind of horror is going to await you there. But there are two safe rooms in the game designed to make you feel safe and protected. When you enter them, a calming music track plays in the background. If you play as Jill, your partner leaves useful stuff for you in there. You can also save your game. The transition from these safe rooms to the creepy dangerous corridors of the mansion always accentuates the safety and horror of each respective location more, and adds more depth to the game’s atmosphere. Dark Souls’ Bonfires also play the same role as the safe rooms in Resident Evil.

The point is that if you create horror environments, but designate small locations in them in which the player feels absolutely safe, chill and even hopeful through mundane familiar elements, the constant transition between the two can create atmosphere. I remember the first time I entered a Resident Evil safe room and interacted with a lantern, the game said something like: “The lantern’s warm light makes you feel safe.” That one line, combined with the calming music and the tense zombie action and inventory management that came before it, made me appreciate this little room so much and form an emotional bond with it.

This mundanity can also manifest itself in a character, rather than a location. For example, the creepy trader guy in Resident Evil 4 is a beacon of mundanity in a sea of horror. Seriously, why should someone in that location be involved with handling a business?

Another example is Norton Mapes in F.E.A.R. F.E.A.R. is a very linear, serious and gloomy horror game that doesn’t have the transitory nature of the games mentioned so far (unless you count the juxtaposition of military aesthetics with Japanese ghost horror as such an example), but the mundane is represented in the form of an overweight, whiny, cartoonish and out of place programmer called Norton Mapes. Norton Mapes is visually different from all the elements in the game, as if he’s a sitcom character who has lost his way and ended up in an FPS horror game. Most of the game’s fans hate him – and to a degree, that’s deliberate – but his presence in such gloomy and dark environments adds a strange sense of atmosphere to the game. The moments you interact with him act as the moment of “transition to the mundane”.

Conclusion

In essence, the key to crafting a truly atmospheric gaming experience lies in the deliberate orchestration of transitions. The effectiveness of this approach is underscored by its ability to generate stark contrasts, thereby intensifying the emotions associated with each distinct location. It’s crucial to recognize that the power of atmospheric horror thrives on unexpected shifts. Unlike the predictable horrors of a hellish landscape, the placement of a subtle portal to hell within the tranquility of Stardew Valley would leave an indelible mark on players’ psyches, haunting their thoughts for years to come.

This is not an endorsement for Stardew Valley to take such a drastic turn, but rather a testament to the profound impact that calculated transitions can have on the overall gaming experience. In the realm of horror, the adage ‘less is more’ holds true; a careful blend of 80% mundane moments and 20% well-timed scares can prove more evocative than a relentless onslaught of horror. It’s the artful balance and strategic use of transition that ultimately elevate a game into the realm of truly memorable atmospheric horror.